Posts Tagged ‘Performance Management’

Yes, You Can Stop Doing That

Before COVID-19, education leaders prided ourselves in being goal oriented professionals, doing everything in our power to support student success. Working in schools, districts, CMOs, state departments of education and in supporting organizations, we took pride in our commitment to do whatever it takes, knocking through barriers, and always maintaining high expectations for ourselves and others.

But now, that day is over. Or at least on pause. We are balancing full days of meetings with full days of homeschooling our own children, we are nursing ourselves or our families back to health, we are facing fear, frustration, and grief. Our lives have changed and so too must our expectations for ourselves and for others.

Talking with talent leaders across the country, We’re discovering that many simply need to hear, “You can stop doing that. It will be ok.” It’s time to re-prioritize and focus on the purpose of your work, not stay wed to the original plan or program. Schools can be our model. Teachers and principals are learning a whole new way to educate students. They are no longer teaching the same lesson plan, but they are working toward the same standards, ensuring that students are able to learn and grow. District and network leaders need to do the same.

For example, we were recently asked by talent leaders in both a big urban district and in a big charter network about how to continue their robust evaluation systems. While we firmly believe in systems of teacher development, evaluation, recognition and pathways (and have spent most of my career focused on them), now is the time to pause and reassess. It’s the time to ask yourself what the ultimate purpose of your work is and if your system is doing that now. It’s time to simplify and focus on achieving that original purpose, not to MacGyver a complicated and time consuming process. When we talked with leaders about their multiple measure evaluation systems we were direct – your student achievement measures based on interim data aren’t going to be accurate and won’t help teachers get better, so don’t do that. Your families don’t have time to give feedback on teachers, so don’t do that. Your teachers aren’t teaching in ways that align to the observation rubric and had to learn this new method in a day, so don’t do that. Instead, coach and support the adults to do the best they can in a tough situation so they can be their best for kids.

The purpose is always to support people to get better and stay longer.

Is your system doing that now?

As a talent leader, we recommend focusing your time and energy into five priorities:

- Communicate clearly and transparently – State what you know and what you don’t yet know. Be clear about the values that are driving decisions and what is being prioritized right now. Be real about your own fears and your own optimism. And find ways to connect. You can share a video, hold office hours or reach out one on one. In doing so, always focus on the employee’s needs as a person.

- Listen to and support your school leaders – School leaders are struggling through this time, navigating their own emotions and disappointments, and those of their teachers, students and families. Be responsive to their needs and make them your priority. When you need their input, make it as easy as possible for them. Give them a clear proposal and let them react.

- Retain your staff – Have “stay conversations” so people know they are valued and appreciated. Ask them directly through conversations or surveys what their plans are for the fall. Consider how to retain salaries through limited budgets and how to incentivize people through non-monetary compensation.

- Recruit and hire new candidates – Hiring will need to move online, but keep the process moving. Think about how to get hiring managers comfortable granting offers remotely and how to get candidates comfortable to accept offers. Identify how to bring your schools’ unique culture to candidates. For more, check out TNTP’s Virtual Hiring Guide and Fast Company’s article on unconscious bias.

- Recognize and celebrate people – Consider cancelling performance based rewards based on results from 2019-2020 and re-use these funds to recognize teachers now (or returning teachers in the fall). Identify ways to say thank you for the hard work and creativity people are bringing to the work. For example, a personal thank you message, a take-out restaurant gift certificate or a retention bonus at the start of next school year are all effective in letting people know they are appreciated.

As our fearless talent leaders, we want to say thank you for taking care of the adults so they can take care of the children. And, yes, you can stop doing that.

From Puzzling to Problem Solving: My Growth Over Five Years at Hendy Avenue

My history with Hendy Avenue Consulting began at a coffee shop on the Lower East Side one afternoon in late 2014. I didn’t know what to expect, but thought it would be great to reconnect with Sarah, share a bit about what I had been up to professionally, hear about her work starting a consulting business and maybe, just maybe, start a conversation about how I could fit in the picture.

I couldn’t have imagined what was to come: five years at Hendy Avenue made up of great client partnerships, numerous high-impact projects impacting thousands of teachers, leaders and students, hundreds of hours video-conferencing, and a growing and tremendous team of colleagues and friends. We’ve built something special, and I couldn’t be more proud.

I’m so fortunate to work in an environment that not only supports professional (and personal) growth, but prioritizes it. It’s hard to narrow down, but here are four big lessons I’ve learned during my time at Hendy these last five years.

1. Take a Breath & Think

Prior to joining Hendy Avenue, my professional responsibilities consisted mostly of doing, rather than thinking. That’s not to say I did my work mindlessly, rather the focus and value-add of my contributions were grounded in producing materials, knocking things off a to-do list, and frankly working longer and harder than others. This efficiency-focused reality served me well in prior roles as a teacher and district administrator and during both stints in graduate school while working full-time. I thrived putting out fires and meeting tight deadlines–it was energizing. And look, I still love making and completing to-do lists, but the hyper-focus on efficiency limited the depth of my understanding of the tasks at hand, the quality of the ultimate end products, and the legacy of my work once I had moved on.

Now, as a more mature professional and seasoned consultant, I’ve retrained myself to take a breath and prioritize thinking as the real work, and as a result, my work is better, clients are happier and the impact on leaders, teachers and students is greater. Please know that This. Was. Not. Easy. (Sidenote: It’s still not easy). I was the archetype of young, type-A, overachieving, borderline obsessive, complete the task and your feelings be damned worker-bee. My own self-worth and value were tied-up in finishing the job. In fact, I remember early on into the role at Hendy just sitting at my desk with what felt like NOTHING to do. My inner-monologue wasn’t pretty: “I’m a waste. What value am I providing? Am I really doing anything to better serve students?”.

With time, and lots of other quiet moments, this role has shown me that yes, sometimes you need to put out that fire, but more often than not, we are brought into work precisely for our thinking, for our fresh and focused take on things made possible by the time and space we have as outsiders to pause, breathe, and think. When you’re treading water to stay afloat, you’re not best positioned to survey the ocean to find the route to safety. From the shore, surveying all that you can, the path becomes clearer.

I know now that my value-add is not just additional capacity–it’s asking tough questions, aggregating data, absorbing information, drawing from experience, guiding decision-making and making strong recommendations precisely because I intentionally hold sacred time and space to be strategic. So what can you do? Block time in your calendar for strategic planning/problem solving, journal or record a voice note of your questions and theories of the case, work with partners to pressure test ideas and most importantly, know your work and value are greater than a completed to-do list.

2. Build Comfort in Ambiguity

With all that time and space to think, you’d imagine the answers come easily. Sometimes, that’s true–we can identify a problem and name the best solution after a quick introductory call with a client. But usually, even if the answer is clear, the route to success is cloudy. Organizations are complicated, even the best ones; look under the hood and something, somewhere is a #hotmess–it’s the nature of people working together.

Five years ago, when confronted with a less than clear road forward, I would have likely either (1) built a quick plan based on instinct or (2) retreated from taking a position and deferred to others, not yet confident to survive the painstakingly vulnerable moment of someone publicly disagreeing. If ambiguity persisted, I would feel like a failure, thinking I was not providing my clients what they needed, deserved, and for some reason, were paying for!

With time, I’ve learned to sit with ambiguity, become less judgmental about it, acknowledge it, respond to it, and sometimes leverage it as an opportunity. This comfort didn’t happen overnight; in many regards, it’s grown alongside my work (and persistence) with clients.

As I’ve wrestled with making decisions within confusing and changing contexts, a few tried and true techniques have proven fruitful:

- Return to the overarching purpose and big goals: Start projects with a clear, compelling goal. Knowing what success looks like will help you make decisions that drive toward that end goal, keeping you on track, even when the view ahead is blurry.

- Assess the current moment in time within the larger lifespan of the project: Is this truly critical? Where are we in the scope of big decisions to be made? What are the implications of moving quickly/slowly? What’s within our locus of control that we can act on now?

- Consider all the possible theories of the case: In any confusing situation, there are many potential causes and solutions. Push yourself to see the situation from multiple points of view, pressure test theories with colleagues and game out possible paths forward, considering the pros/cons for all stakeholders.

- Pessimistically plan: Intentionally think about likely obstacles then developing ideas for how to pre-empt or respond.

3. Invest in Relationships

If you couldn’t already guess, I love a good project plan; I live for a beautiful Excel spreadsheet. But it has been obvious over the past five years that relationships, not these tools, make the work happen and achieve success.

On one hand, our ability to analyze data, review policy, design communications, and make recommendations rests on knowing the stakeholders involved—their interests, expertise, passions and limitations—which can’t live on a spreadsheet.

Second, and maybe more important, this work is really personal–it’s about kids’ and their life opportunities. I think about my former students every day; my heart still aches for the pain they felt 10+ years ago when they fell on the playground and I remember joyfully the smile that came across their face after reading aloud their own writing during a publishing party. So many of our clients and partners have similar driving memories–of past students or their own children–making our work to better teaching and learning incredibly meaningful and high-stakes.

Talent development programs too are incredibly personal. The average American spends 90,000 hours at work over their lifetime. So much of our identity and self-worth is tied up in our jobs. As anyone who has lived in New York City knows, the most common question you’re asked after meeting someone is: “what do you do?” As a result, any efforts to define, develop and reward excellence at work can strike at the core of who we are and how we feel.

Here are four strategies for building and maintaining relationships that I’ve found to be helpful:

- Be authentically yourself. One, you deserve to always be your true self. Two, you’re always modeling behavior for others, so set and hold the expectation. Three, people like other people who are comfortably themselves; think about a time you disagreed with someone, you probably continued to respect them if you sensed they were being honest. If you felt like they were trying to game the system or play politics, you probably don’t want to re-engage with that person unless you have to, regardless of the content of their opinion.

- Be intentional about knowing people, especially when working virtually/at a distance. Building strong relationships won’t just happen. Think about ways you can plan routines and systems that are inclusive, review how your time is spent and with who, audit the airtime of folks in meetings, and reference the accomplishments of others. Know the names of your client’s kids. Ask about upcoming plans to travel to Mexico. In other words, be a real person at work. I can’t encourage this enough, but take notes–you probably do during all other work meetings and engagements–why not now? I’m horrible at remembering names and worse with birthdays and anniversaries, so instead of not knowing, I write them down. My Outlook calendar is a color-coded Rosetta Stone for my life, and the 10 seconds it takes to set a recurring reminder for someone’s birthday goes a long way in showing colleagues and clients that I value and care about who they are.

- Make yourself part of the team. It can be difficult to feel part of the team when you’re (1) external to the organization (2) not physically situated with others and (3) present for some, but not all key meetings and events. Teams may not sit in Office Space-style cubicles and have to write TPS reports anymore, but so much of a group’s culture building happens around the proverbial water cooler. So what can you do?

- Do your homework and know what’s happening in town: the weather, the hot new restaurant opening, the big game that weekend; all are great for making yourself part of the team. Pro-tip: set up Google alerts!

- Make a concerted effort to learn and use the language used by your clients: Are they students or scholars? Principals or School Leaders? What’s the funky acronym for their central office teams? These little cues help you meld into the team and live in their world comfortably, even if it’s only for a few hours a week.

- When possible, invest time (and money) in being physically present: go to team happy hours and lunches; join weekly team meetings and spend a day working from the office–you may even be there for the creation of a lasting inside joke.

- Be vulnerable, appropriately. Vulnerability is hard for many of us, especially achievement-oriented, type-A folks who lead teams. We’ve been (unfortunately) conditioned to think that we must be confident, direct and all-knowing at all times or face the wrath peers who hold you in low regard. Not only does this limit our ability to be authentic and build relationships, it presents a damaging model for colleagues who are likely to replicate your behavior. Take the risk and be vulnerable when the moment calls for it. This could look like telling a deeply personal story about why the project you are leading is meaningful to you or sharing lessons learned from a time you failed miserably. Keep in mind however that the benefits of vulnerability have limits, and efforts must stay within the standards of your professional context. I don’t encourage starting all meetings with a trust fall exercise or co-opting a team retreat to complain about your neighbor’s dog. Instead, productive vulnerability humanizes you and connects to the work.

4. Implementation > Design

Talent leaders often spend so much time working to craft “perfect” rubrics, surveys, rewards and retention techniques. While these factors matter a great deal, they are usually not the tipping points between success and struggle. What matters more is the depth, breadth and quality of implementation.

This reality comes up most when I think about projects that fell short of their intended outcomes. Did I spend my time wisely? How well did I prioritize building internal capacity and skill to execute? With one client team for example, we had some of our best plans and meetings, smartest designs, and the beginnings of strong relationships with stakeholders across the organization. I honestly re-use some of the content from those evaluation design meetings because I think they were our strongest to-date. And yet, we had to pause, then end the project early, well-before we had met the intended outcomes because internal capacity was not there.

As we stew on how to find the right balance, here are a few recommendations for successful implementation:

- Over communicate the why: you can never, never, never over-communicate the rationale for programs and decisions. For those in the work daily, the outcomes we seek can be obvious and the rationale behind decisions clear. But for most, especially folks on the receiving/participatory end of our projects, they have thousands of other things to worry about and therefore need to be constantly brought back to the overarching purpose and compelling reason for the program/change/initiative you are leading.

- Start from the ground up: this could also be called, “don’t make assumptions”. It is easy to make generalizations about what stakeholders want, whether it be a firm’s employee value proposition, retention strategy, or compensation model. Yes, you should read what Vox says about Millennials in the workplace or Gallup’s best methods for responding to Q12 survey data—those are helpful, but as a floor, not the ceiling. The best outcomes stem from going directly to the source, the end users or folks who will be impacted by the policies and programs we manage and asking, “What do you want?” “Would this be meaningful?” “What matters most/least?”

- Pilot, pilot, pilot: Everyone underestimates the lift required to successfully implement a change. I can’t count the number of times a C-level leader has said, “we’re really good at instructional coaching” or “our data systems are strong” to only have that same strength become THE roadblock to success. The key to avoid this trap is investing the time, resources, energy and attention to robust piloting. There is no better way to learn what will and won’t work than testing within your context. Do it early and often.

So what now? While the field always moves forward, systems change over time and life circumstances always bring surprises, the one constant is the opportunity to grow and develop. I’ll just have to keep learning. Here’s the next five years and all to come that can’t even be imagined. -Grant

Designing Systems to Limit the Impact of Bias

In March, we wrote about how coaches and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice. This critical work by individuals is powerful, but not the only tool available to leaders and policy makers in reducing bias: Specific design elements within performance management systems can help reduce opportunities for bias to impact results.

Drawing upon findings from the MET Study and our practical experience with school systems across the country, we recommend three design features to limit biases:

- Balance with multiple measures: Evaluations that rely on a single input are not only more vulnerable to year-over-year volatility but they present the greatest opportunity for evaluator bias to impact outcomes. Consider, for example an evaluation system with one input, ratings on a common teaching rubric. As evaluators work to determine ratings, their biases can (and will) creep in. Without a second or third objective measure to balance the overall evaluation, the teacher’s rating is subject to the influence of these biases with no checks or balances.

- Utilize multiple observers/evaluators: As with multiple measures, adding additional observers/evaluators increases statistical reliability (reliability = overall consistency of a measure). MET Study authors write: “When the same administrator observes a second lesson, reliability increases from .51 to .58, but when the second lesson is observed by a different administrator from the same school, reliability increases more than twice as much,from .51 to .67.” While districts must wrestle with the best allocations of limited time and resources, there is great benefit to having a second set of eyes on a teacher’s performance.

- Use outcomes-based tools: Many common evaluation instruments measure inputs–the actions taken toward a goal–rather than assessing the desired outcomes. Unfortunately, measuring inputs can yield false positives: a teacher can try a specific approach and receive high marks, even if the strategy fails to produce appropriate student learning. Instead, strong evaluation systems use outcomes-based tools and rubrics that identify observable and measurable behaviors. For example, we’re big fans of the Core Teaching Rubric, which describes with specific language what students are saying and doing at different levels of performance–rather than teacher actions–so that observers can evaluate performance based on what matters most: student experience and learning. By focusing on student outcomes, there is less risk of observers inserting their biases or preferences for a particular instructional strategy. Instead, an outcome-based tool focuses observers on what and how students are learning, which is what matters the most.

While these structural changes alone will not eliminate bias, they can make a big difference. What have you seen be successful in reducing bias in performance management? Let us know in the comments!

Three Lessons for Meaningful Performance Management Incentives

We’re big fans of performance management. We know that for people to achieve their best, they need clear definitions of excellence, resources and tools to achieve that benchmark, and frequent, action-oriented feedback that drives their development. Too often, however, organizations don’t know how to link performance management efforts with valuable incentives for their talent.

Before we dig in, let’s get one thing out of the way: incentives in the workplace are not inherently good or bad. Done well, incentives can be a powerful tool for motivation, recognition and reward. Done poorly, incentives can lead people to feel controlled or set up for failure.

Incentives come in all shapes and sizes but most fit within one of the five Rs:

- Rewards: salary, incentives, bonuses, benefits

- Responsibilities: variety, autonomy, challenge, promotions, learning

- Relationships: coworkers, supervisors, clients, and customers

- Reputations: image, respect, appreciation, feedback

- Rest & Relation: hours, scheduling, flexible, travel, location

So what now? Maybe you want to give a bonus to high-performers, grant newcomers more autonomy or show appreciation to employees who routinely go above and beyond. In any situation, here are three recommendations to help you build a foundation for offering incentives:

- Set achievable, meaningful, and controllable benchmarks for employees. Ambitious goals are great but they should not be impossible to reach. Similarly, desired outcomes must matter to the person and organization. If mission driven, make clear the connection between the individual’s impact and how it helps the the organization get closer to their vision. It may seem obvious, but people also have to know that what they will be measured against can be reached by the levers within their control. We would never evaluate a bank teller by the number of light bulbs that need to be changed monthly, so test your goals to ensure a direct line back to employee actions and responsibilities.

- Know what people want. A huge problem is that organizations generally don’t know what their people want. For example, leaders may assume everyone is motivated by the same things or rely too heavily on what has historically been motivating. Particularly in large or longstanding organizations, there is too much application of the golden rule (treat others as you want to be treated) by decision-makers and not enough of the platinum rule (treat others as they want to be treated). There’s no secret to fixing this problem; you need to do your research (e.g., ask employees, read research on generational shifts, talk to industry leaders) and pilot before full-scale launch. The best approaches customize incentives for specific groups or individuals.

- Keep support and growth at the center. Earning an incentive should not be the end of the journey for your employees. Milestones are important, but should always be coupled with a “what’s next?” conversation so that people feel you are genuinely invested in their growth and development (which we hope you are!) and can tangibly see the road ahead. If one does not yet exist, take the opportunity to co-create. A common pitfall is focusing too much on monetary or extrinsic rewards, sometimes to the detriment of strong intrinsic motivators. Focusing on continual improvement and long-term development will help mitigate this risk.

How have you effectively implemented incentives? What’s been the most interesting outcome? Sound off in the comments below!

Three Steps to Avoid Common Observation Biases

We all have biases. Whether picking an ice cream flavor or choosing to take the scenic route rather than the highway, we all operate with mental models that place disproportionate weight on certain factors that move our judgment in favor of one option when compared to another.

When observing and evaluating teacher practice, there are numerous opportunities for biases to creep in. Just think of all the factors that go into a lesson: the subject, grade, school, teacher, time of day, lesson structure, materials used and more. An observer may think to themselves, “the students were well-behaved for the first class right after lunch”. A different person observing that same lesson may think, “if I was teaching this class, I would have used a different text.” Both of these sentiments may be true, but they have to be placed aside before conducting a visit so that observers can focus on objective teacher and student actions.

In short, great observers, coaches, and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice.

Common biases include:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions,

- Halo effect: the tendency for a person’s positive or negative traits to “spill over” from one area of their personality to another in others’ perceptions of them, and

- Mirror bias: the tendency to judge performance as “good” if it is “like I would have done it.

A full table of common observer biases with examples can be found here: Observer Bias Examples

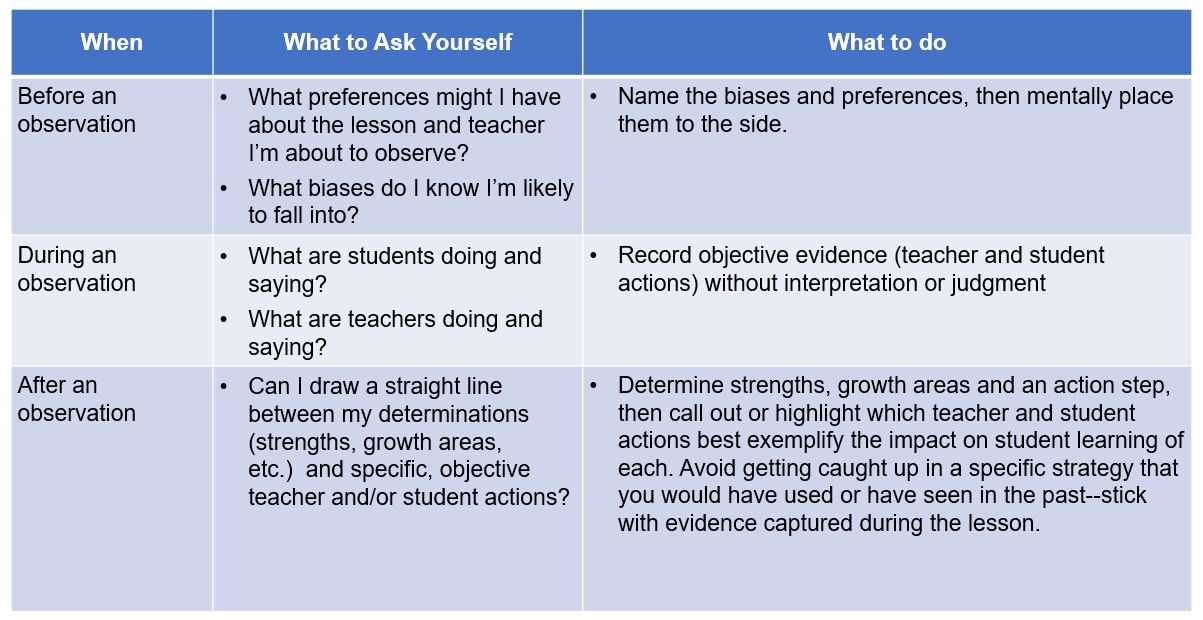

In order to mitigate the impact of these biases, great observers should ask themselves three questions:

Round 3: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

In our previous two posts (here and here), Sarah and Grant shared reflections on the past year and projects they are looking forward to in the coming months. To bring us home, Jessica shares lessons learned on working through complexity and opportunities to lead with appreciation.

What I learned: I have spent most of my career in education supporting and working in large bureaucracies, namely large urban districts and state education agencies. Just prior to joining Hendy Avenue I was in senior leadership in one of the largest school districts in Ohio. Each of the organizations I’ve worked with in the past have faced challenges, and I tended to chalk those up to organizational complexity, and the difficulty that comes with arriving at solutions when you must invest a large number of people and perspectives in the strategies. After spending my first year with Hendy working with diverse organizations and districts, I came to appreciate that the challenges I faced in past contexts are not so different from those faced by clients of all sizes. I’ve learned that it’s often not only the scale and bureaucracy that causes the challenges we face in K-12 education, and that we can learn a lot from organizations of different sizes and types in finding solutions. As we partner with our clients this year, we are excited to continue to bring lessons learned from all shapes and sizes of districts, states, schools and networks to arrive at solutions to problems.

What I’m excited about: I am so happy to get to continue to partner with Independence Mission Schools in Philadelphia. Having attended Catholic schools as a child, I have a great appreciation and admiration for the work IMS is doing for some of Philadelphia’s most deserving students. We learned a lot from IMS’ leaders and teachers as we supported them last fall to implement their new instructional framework, and to modify that framework to fit their Catholic culture. Now, I’m excited to continue to support IMS leaders as they deeply invest in teachers through teacher leadership. This project has been a welcome opportunity to explore how others are solving a problem, learn more about the context, strengths and opportunities in IMS schools, and devise a program that makes a difference for teachers, and students, across the network.

Put Excellence at the Heart of Performance Management

Performance management, at its core, sets expectations. It puts a stake in the ground for what “good” looks and sounds like in the classroom and serves as the baseline of teacher observation rubrics. Effective performance management is more than diagnosing current performance; it supports teachers to articulate an actionable, clear trajectory toward excellence. Ultimately, a vision of good teaching and learning must be at the heart of any performance management system.

Common Pitfall: Framework Without Vision

Too often schools and districts launch a performance management system by creating or selecting a rubric without consideration of core instructional priorities. Enthusiasm and urgency, while helpful, can lead to less than ideal system design.

For example, simply adopting an existing framework because it is “proven” or “research-based” might not actually lead schools and teachers to excellence: what might be excellent teaching in one context might not be true in another setting. Creating a framework from scratch in a vacuum, separate from instructional priorities, isn’t likely to lead teachers to excellence either.

This doesn’t mean that adopting an existing framework is the wrong strategy, or that creating something new won’t get leaders and teachers where they need to be. It does mean, though, that this work must be grounded in the core realities of instruction necessary to move kids.

Ground Performance Management in a Vision for Excellent Instruction

Co-design and co-own by instructional leaders. Defining excellence for as complex a role as teaching requires a team of individuals, with different areas of expertise and focus. While very often, the development of teacher evaluation systems lives within talent/human resources, great systems strategically draw in additional stakeholders. For quality operations, a talent leader should drive and own the design and implementation of a performance management framework. At the same time, this work should be a shared priority between leaders of talent, academics and school management functions in a network or district. Instructional leaders working in schools daily must be the core authors and implementers of expectations for teachers.

Measure what matters. If teachers are held to expectations through a framework that aligns with core instructional priorities, schools are more likely to see improvement in the areas that matter most for students. If a solid instructional vision grounds all decision making, then curricular resources, training, and other supports will naturally stem from that vision. As teachers are supported to meet expectations via appropriate the resources, materials, and training, student learning will flourish.

Lead from your vision. Consider the following questions, and strategically engage others to ensure answers reflect the perspectives of a broad range of stakeholders:

- What are our prevailing beliefs within our system about students, and the role teachers play in their success?

- What do the instructional standards require from our students? And then, by extension, from our teachers?

- In classrooms where good teaching and learning is happening, what are teachers doing? What are students doing?

- How does this differ for different students? Different contexts?

- How do we ensure that the performance management system we design reflects our vision of excellent teaching?

- Who will own this work? How will we ensure that leaders from talent and instruction both continue to be involved?

Let us know what you think in the comments below!

-Jessica