Posts Tagged ‘observation’

Three Steps to Avoid Common Observation Biases

We all have biases. Whether picking an ice cream flavor or choosing to take the scenic route rather than the highway, we all operate with mental models that place disproportionate weight on certain factors that move our judgment in favor of one option when compared to another.

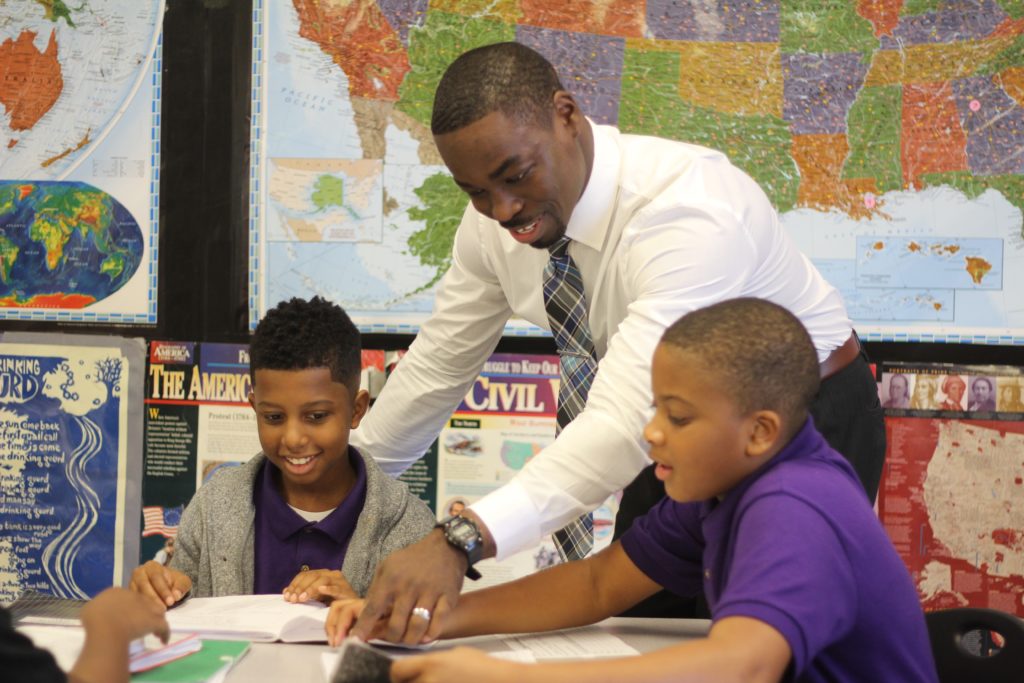

When observing and evaluating teacher practice, there are numerous opportunities for biases to creep in. Just think of all the factors that go into a lesson: the subject, grade, school, teacher, time of day, lesson structure, materials used and more. An observer may think to themselves, “the students were well-behaved for the first class right after lunch”. A different person observing that same lesson may think, “if I was teaching this class, I would have used a different text.” Both of these sentiments may be true, but they have to be placed aside before conducting a visit so that observers can focus on objective teacher and student actions.

In short, great observers, coaches, and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice.

Common biases include:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions,

- Halo effect: the tendency for a person’s positive or negative traits to “spill over” from one area of their personality to another in others’ perceptions of them, and

- Mirror bias: the tendency to judge performance as “good” if it is “like I would have done it.

A full table of common observer biases with examples can be found here: Observer Bias Examples

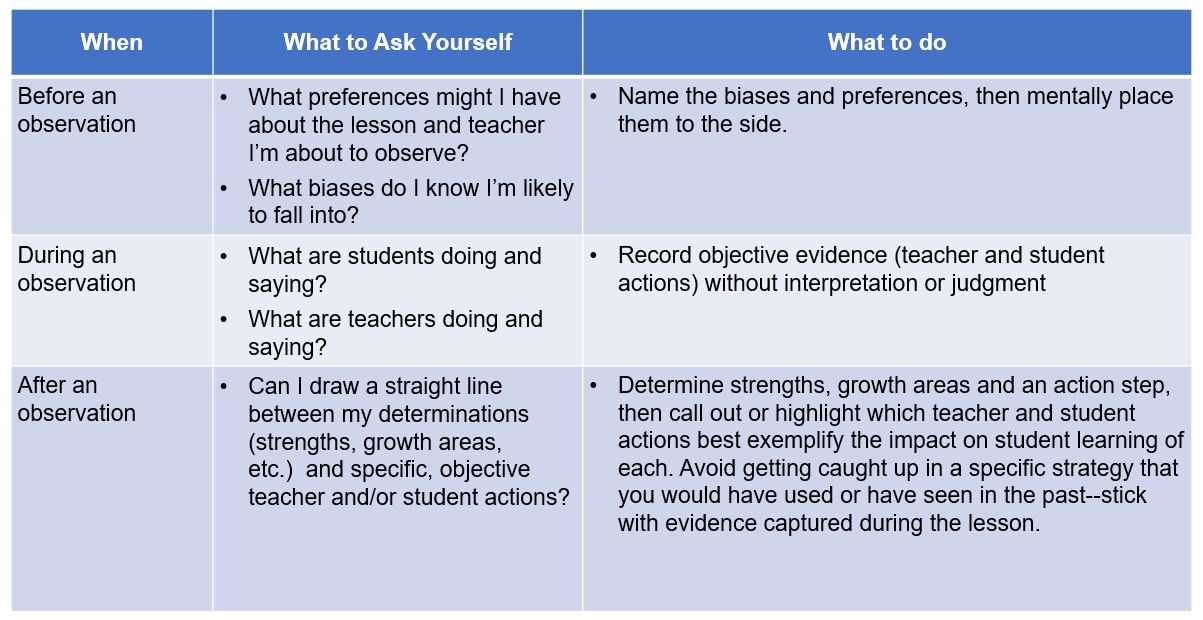

In order to mitigate the impact of these biases, great observers should ask themselves three questions:

Put Excellence at the Heart of Performance Management

Performance management, at its core, sets expectations. It puts a stake in the ground for what “good” looks and sounds like in the classroom and serves as the baseline of teacher observation rubrics. Effective performance management is more than diagnosing current performance; it supports teachers to articulate an actionable, clear trajectory toward excellence. Ultimately, a vision of good teaching and learning must be at the heart of any performance management system.

Common Pitfall: Framework Without Vision

Too often schools and districts launch a performance management system by creating or selecting a rubric without consideration of core instructional priorities. Enthusiasm and urgency, while helpful, can lead to less than ideal system design.

For example, simply adopting an existing framework because it is “proven” or “research-based” might not actually lead schools and teachers to excellence: what might be excellent teaching in one context might not be true in another setting. Creating a framework from scratch in a vacuum, separate from instructional priorities, isn’t likely to lead teachers to excellence either.

This doesn’t mean that adopting an existing framework is the wrong strategy, or that creating something new won’t get leaders and teachers where they need to be. It does mean, though, that this work must be grounded in the core realities of instruction necessary to move kids.

Ground Performance Management in a Vision for Excellent Instruction

Co-design and co-own by instructional leaders. Defining excellence for as complex a role as teaching requires a team of individuals, with different areas of expertise and focus. While very often, the development of teacher evaluation systems lives within talent/human resources, great systems strategically draw in additional stakeholders. For quality operations, a talent leader should drive and own the design and implementation of a performance management framework. At the same time, this work should be a shared priority between leaders of talent, academics and school management functions in a network or district. Instructional leaders working in schools daily must be the core authors and implementers of expectations for teachers.

Measure what matters. If teachers are held to expectations through a framework that aligns with core instructional priorities, schools are more likely to see improvement in the areas that matter most for students. If a solid instructional vision grounds all decision making, then curricular resources, training, and other supports will naturally stem from that vision. As teachers are supported to meet expectations via appropriate the resources, materials, and training, student learning will flourish.

Lead from your vision. Consider the following questions, and strategically engage others to ensure answers reflect the perspectives of a broad range of stakeholders:

- What are our prevailing beliefs within our system about students, and the role teachers play in their success?

- What do the instructional standards require from our students? And then, by extension, from our teachers?

- In classrooms where good teaching and learning is happening, what are teachers doing? What are students doing?

- How does this differ for different students? Different contexts?

- How do we ensure that the performance management system we design reflects our vision of excellent teaching?

- Who will own this work? How will we ensure that leaders from talent and instruction both continue to be involved?

Let us know what you think in the comments below!

-Jessica

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part II: Raising Rubric Rigor

This post is the second in a series on how innovators are reimagining the design and implementation of evaluation and development frameworks. To read our first post in the series, on the impact of frequent observations, click here.

Most teacher evaluation systems today include direct observations of teacher practice by an administrator, in which the administrator determines ratings by assessing what they observed against a common performance rubric. It is challenging to capture the complexity of teaching in a single document, however strong rubrics have the capacity to set clear expectations, establish a common language, and chart a course for development over time.

During our work with school systems across the country, we have seen a few common challenges with widely-used rubrics:

1. Structure: Rubrics can be too long, wordy, and easy to master.

When rubrics are too lengthy, they can be overwhelming or intimidating to educators, fail to prioritize high-leverage teacher actions over lower-impact strategies, take too long for observers to complete and are challenging to norm across multiple raters. Additionally, when rubrics are too “easy”–that is when basic instruction with minimal impact on student learning aligns to language at the highest levels–we rob educators of a true pathway for growth in their careers and limit their potential for excellence.

2. Framing: Rubrics generally focus only on teachers.

When rubrics describe only what teachers are doing and saying they fail to take into account what matters most: the impact of instruction on students. This can limit the value of observation feedback and lead to misalignment between observation ratings and other components of an evaluation framework.

3. Content: Rubrics are often not aligned to today’s raised academic expectations.

When rubrics do not call for rigorous instruction aligned to core content standards (Common Core, Next Generation Science, etc.) they miss the opportunity to set expectations for learning at the appropriate bar. Similarly, as our knowledge of social-emotional learning, cultural competency, and technology expand, many rubrics have yet to adapt and account for new knowledge and skills.

In the face of these challenges, innovators are creating a new normal for observation rubrics. Through our partnership with school systems across the country, we have seen that there is no one right way or perfect rubric. Rather, systems need to consider their unique culture, expectations, observer skill level and existing structures to find or develop a rubric that will work best for them.

DREAM Charter School: DREAM prioritized finding a streamlined observation rubric that would be appropriately rigorous as teacher advances along their career while less cumbersome than the tool they had previously been using. Following research into available tools and piloting of a select few, DREAM identified the TNTP Core Teaching Rubric as the right resource: it was aligned to academic content standards, written in the form of student outcomes, and best of all, was only four pages long! DREAM revised some language to incorporate school-specific competencies that drive their unique student and adult culture. Following the first year of implementation, nearly 80% of teachers said the rubric defines excellent instruction well.

KIPP Houston Public Schools: The original and largest KIPP region is currently piloting the Reach to Rigor rubric, a new tool created in-house that defines academic and cultural expectations for teachers and students. The rubric is broken down into four parts with only the most critical components of great instruction included. The rubric language also includes both teacher and student actions, to ensure that instructional moves by the teacher are only deemed high-quality if they have the desired effect on student thinking and behavior.

Achievement First: One of the first movers in formalizing a career pathway for teachers, Achievement First has refined their approach to observation and feedback over time. The network developed and launched an updated AF Essentials Rubric that was intentionally designed to be concise, clear, focused on student actions. The rubric is aligned to the Common Core and expectations of Advanced Placement courses, shifting more emphasis to intellectual rigor and deep student thinking. The rubric includes both “foundational” (e.g., tight classroom or kids on task) and excellence (e.g., investment and deep student thinking) criteria.

What are other innovations in observation rubrics? Add your ideas and/or experiences in the comments section below.

5 Strategies for Scaling Effective Coaching

Our team spends a lot of time thinking about how to develop teachers. We believe that investing in the professional growth of teachers has the potential to dramatically change the landscape of education in our country and the lives of millions of children. While school systems across the U.S. spend billions of dollars annually on teacher professional learning and development we have little proof of their efficacy (The Mirage, TNTP 2015).

Given this context, we were thrilled to read a new study, The Effect of Teacher Coaching on Instruction and Achievement by Matthew Kraft and Dylan Hogan of Brown University and David Blazar from Harvard University. Kraft and his team conducted a meta-analysis of 37 studies and found coaching programs to positively impact instruction (.57 standard deviations) and student achievement (.11 standard deviations). The authors offer the following summary:

The results of our meta-analysis suggest that teacher coaching programs hold real promise for improving teachers’ instructional practice and, in turn, students’ academic achievement. These findings provide strong motivation to invest in efforts to scale up teacher coaching models, and to expand and improve upon the existing research base.

Effective Coaching

The authors characterize the coaching process as one where instructional experts work with teachers to discuss classroom practice in a way that is:

- Individualized: one-on-one sessions

- Intensive: frequent interaction between teachers and coaches (e.g., at least every couple of weeks)

- Sustained: coaching support over an extended period of time

- Context-specific: coaching on their practices within the context of a teacher’s classroom

- Focused: teachers and coaches engage in deliberate practice of specific skills

These findings support much of the work we have done with school systems including KIPP Austin Public Schools, DREAM Charter School and the Cleveland Metropolitan School District to grow talent through multiple-measure evaluation and development frameworks. Each of these organizations have employed innovations specific to their unique contexts, however common across all approaches is a theory of change that recognizes the critical role coaches play in moving teacher practice and ultimately student outcomes.

Scaling Systems of Effective Coaching

One of the most important insights in the analysis is data suggesting “that coaching can have an impact at scale” but that scaling-up programs (to more than 100 teachers) is challenging, particularly in building a cohort of capable coaches and in establishing strong teacher buy-in.

From our experience, these two factors matter mightily. There are certainly pockets of excellent coaching in every school system, but the real challenge of scale is consistency of implementation. Here are five strategies for solving the scale-up challenges described by Kraft, Blazar and Hogan:

1. Establish a common definition of excellence: Coaching is incredibly hard work as it requires deep content knowledge, pedagogical expertise, emotional intelligence and strong interpersonal communication skills. One the best steps we can take to set coaches up for success is adoption of a clear definition of excellent teaching (e.g., a robust rubric or vision of excellence document). In establishing a common bar of quality of important instructional practices and a common language, coaches and teachers have a clear development road-map to work along. You can read more about strong observation rubrics in this March 2017 post.

2. Make Tools Available: Great coaches need tools to guide their learning and development. School systems should develop and train leaders on a common observation debrief protocol or conversation guide such as Paul Bambrick’s 6-Steps to Effective Feedback or the TEF Debrief Planning Guide to structure coaching conversations. Systems for capturing, analyzing and sharing observation data including observation ratings and feedback are also vital for supporting coaching efforts.

3. Invest in ongoing leader development: Often lost in conversations around teacher professional development is the importance of ensuring professional learning for those responsible for coaching teachers. These professionals warrant the same level of thoughtful support. Summer is a great time to bring coaches together for intensive training but without ongoing follow-up, development can be lost or minimized. Managers of coaches should have talent development within their core responsibilities including time for managers to observe and support school leaders/coaches working with their teachers.

4. Build a Culture of Transparency and Continuous Improvement: Ultimately the work leaders do coaching teachers is only as impactful as the level of trust and partnership teachers feel in the relationship. Transparent communication of the “why” and “how” of key policies along with timelines, goals, and progress to-date is essential for successful long-term investment. Gathering frequent feedback with public recognition of the findings and appropriate next steps will build a culture of continuous improvement.

5. Phase-in implementation: As noted in the study, working one-on-one with any person over a sustained period requires an investment of time and money. Certainly shifting funds from less effective professional development activities toward coaching is a strong first step. Another strategy is to phase-in implementation of a coaching program to build capacity, gain early wins, expand the coalition of supporters, and prove the value of the financial investment. We suggest system leaders identify the core problem they are hoping to solve, then target the first phase of implementation toward that issue. For example, if a system seeks to solve the challenges that arise from new teachers lacking foundational classroom management skills they can launch a coaching program focusing on that subset of teachers. Over time, coaches could roll-off and target other groups of teachers for support or the program could expand with the hiring of additional coaches.

What approaches to coaching teachers have you seen work well? How have you built a cohort of strong coaches and/or invested teachers? Let us know in the comments below!

Great Leaders, Great Teachers: How Cleveland Metro is Investing in Leaders

In response to Race to the Top, many states, including Ohio, revised state statutes requiring school districts to develop new evaluation models. In a collaborative effort, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District and the Cleveland Teachers’ Union developed the Teacher Development and Evaluation System (TDES).

We partnered with the talent team at CMSD to develop tools and trainings designed to enhance administrators’ ability to successfully evaluate and develop their teachers. We began the engagement with a robust review of existing research and best practices in order to establish a clear description of the knowledge and skills necessary for leading effective observation and feedback.

Following stakeholder review and investment in the new district-wide expectations, we established a theory of action for building administrator capacity across the district, developing an aligned scope and sequence of training modules aimed at achieving CMSD’s goals. Each training module focuses on both observer calibration and quality feedback for improvement, sharing tools and protocols aimed at bridging the learning into the daily practice of administrators.

Taken together, these training modules provided administrators regular opportunities to reflect on and hone their practice as instructional leaders, improving teacher quality and ultimately, the achievement of students across the district.

Coach's Corner: Book Review of Get Better Faster

We  all know that teaching is hard, but being a new teacher can sometimes seem downright impossible. Fortunately, Paul Bambrick-Santoyo has laid out a critical tool for driving the professional growth of new teachers in his latest book, Get Better Faster: A 90-Day Plan for Coaching New Teachers.

all know that teaching is hard, but being a new teacher can sometimes seem downright impossible. Fortunately, Paul Bambrick-Santoyo has laid out a critical tool for driving the professional growth of new teachers in his latest book, Get Better Faster: A 90-Day Plan for Coaching New Teachers.

The Chief Schools Officer for High Schools and K-12 Content Development at Uncommon Schools, Bambrick-Santoyo has become a leading figure in school leadership, professional development, and data-driven instruction. In Get Better Faster, Bambrick-Santoyo lays out a compelling case for how school leaders, administrators, and coaches can guide new teachers to develop their instructional practice efficiently and effectively, making an immediate impact on the lives of their students.

In focusing on new teacher quality, Bambrick-Santoyo recognizes the immense power teachers have in shaping the lives of their students as well as the corresponding responsibility for coaches to guide their teachers to success. Across the nation however, Bambrick-Santoyo notes:

Teachers aren’t receiving much coaching. As a consequence, educators are very rarely asked to practice the micro-skills that will make them better at teaching–especially not under the supervision of an expert who can help them get better on the spot. Unlike soccer players, actors, or doctors, teachers tend to have to learn on their own.

It should be as no surprise to know that many U.S. teachers leave the profession within their first few years of teaching, often in response to the lack of support needed to feel and be successful.

Get Better Faster is built off of the guiding concept that what is actionable is “practice-able” and therefore able to respond to effective coaching.

Bambrick-Santoyo begins by identifying and unpacking three core principles of coaching:

- Go Granular: break teaching down into discrete skills to be practiced successively and cumulatively.

- Plan, Practice, Follow Up, Repeat: Coach a teacher through effective practice.

- Make Feedback More Frequent: Make the most of every observation by increasing the frequency of feedback.

The text then moves into a detailed scope and sequence for rapidly improving teacher practice. Bambrick-Santoyo outlines how to support teachers with classroom management and rigorous instruction by identifying a prioritized list of key action steps with guidance on when to use the strategy, what it looks/sounds like, and scenarios for practicing. For example, the scope and sequence for classroom management begins with “routines and procedures 101” then scaffolds up to using a “strong voice”, giving clear directions, and actively scanning the room. For instructional rigor, the sequence guides leaders through coaching on lesson planning, use of exemplars, meaningful independent practice and methods for checking for understanding.

Like his prior publications, Get Better Faster is full of strong real-classroom examples, recommendations for implementation, printable resources and a thorough video library of great coaching in action. Leaders across the country working with new teachers will be well-served by the expertise Bambrick-Santoyo has captured in this book and many students will be grateful for their doing so.

We have used the concepts and resources in Get Better Faster throughout our work with many clients including the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, New York City Department of Education, and DREAM Charter School. For more information about those projects, visit http://hendyavenue.com/clients/.

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part I

Encouraged by Race to the Top and the Department of Education’s ESEA waivers, teacher evaluations moved into the education policy limelight during the last decade. Dozens of states updated antiquated systems–usually nothing more than a checklist of low-impact items–into multiple measure approaches with student achievement a preponderant component.

While this was a critical first step, too many frameworks failed to prioritize teacher development, becoming compliance exercises for school leaders. Fortunately, innovators across the country are re-imagining the design and implementation of evaluation frameworks into evaluation and development frameworks.

Over the next few months, we will share examples of these innovations from various partners and leaders in the field. In our first post on the topic, we share how two school systems are using frequent, unannounced observations to drive teacher development.

The Power of Frequent Observations

Observations have historically been rather formal exercises, often with scheduled pre- and post-conferences designed to provide teachers and administrators with dedicated time to plan for and then reflect upon a lesson. While there is immense value in these face-to-face interactions, they come with limitations. The heavy time burden for scheduling and completing these meetings limits the frequency in which they can occur. Often, administrators will only be able to visit one to three times in year, reducing the impact of their feedback and diminishing their ability to provide meaningful follow-up support. Announced observations also increase the opportunity for a lesson to be less reflective of a teacher’s true daily practice.

Many school systems across the country are taking a different approach to observations:

The Teaching Excellence Framework is used by more than a half-dozen independent charter schools in Delaware as part of the state’s educator evaluation regulation (Chapter 12, subchapter VII, Section 1270(f)) that allows LEAs to apply to implement an alternative teacher evaluation system. The framework was designed with frequent lesson observations at the heart of the overall plan for teacher development. Observations are 15-20 minutes in length and occur at least 8 times throughout the year. Following each observation, the observer utilizes the Teaching Excellence Rubric to assess the evidence in the lesson. A face-to-face debrief conversation occurs within one week in which the teacher and school leader determine concrete, actionable next steps. As a result, 95% of teachers surveys reporting feeling ‘positive’ to ‘very positive’ about the shift to the Teaching Excellence Framework. You can learn more about the Teaching Excellence Framework here.

Understanding the importance of excellent teachers, in 2014 the DREAM Charter School in New York City set out to revamp their system for teacher evaluation and recognition. Recognizing their teachers wanted more frequent feedback, the design committee at DREAM developed a system that would include:

- Five unannounced observations throughout the year in which a teacher’s manager or a secondary observer determine ratings on the DREAM Observation Rubric

- Bi-weekly unannounced observations in which a teacher’s manager provides feedback and direct support, including real-time coaching (no ratings)

All observations are followed by coaching conversations focusing on strengths and growth areas of the teacher’s practice as well as instructional next steps. Following the first year of implementation, one teacher praised the approach noting “it gives teachers clear take aways and next steps” while another said “it is streamlined [and] it pushes for development.” To learn more about DREAM Charter School, you can visit their website here.

What are other innovations around observation frequency? Add your ideas and/or experiences in the comments section below.