Posts Tagged ‘Career Pathways’

Three Lessons for Meaningful Performance Management Incentives

We’re big fans of performance management. We know that for people to achieve their best, they need clear definitions of excellence, resources and tools to achieve that benchmark, and frequent, action-oriented feedback that drives their development. Too often, however, organizations don’t know how to link performance management efforts with valuable incentives for their talent.

Before we dig in, let’s get one thing out of the way: incentives in the workplace are not inherently good or bad. Done well, incentives can be a powerful tool for motivation, recognition and reward. Done poorly, incentives can lead people to feel controlled or set up for failure.

Incentives come in all shapes and sizes but most fit within one of the five Rs:

- Rewards: salary, incentives, bonuses, benefits

- Responsibilities: variety, autonomy, challenge, promotions, learning

- Relationships: coworkers, supervisors, clients, and customers

- Reputations: image, respect, appreciation, feedback

- Rest & Relation: hours, scheduling, flexible, travel, location

So what now? Maybe you want to give a bonus to high-performers, grant newcomers more autonomy or show appreciation to employees who routinely go above and beyond. In any situation, here are three recommendations to help you build a foundation for offering incentives:

- Set achievable, meaningful, and controllable benchmarks for employees. Ambitious goals are great but they should not be impossible to reach. Similarly, desired outcomes must matter to the person and organization. If mission driven, make clear the connection between the individual’s impact and how it helps the the organization get closer to their vision. It may seem obvious, but people also have to know that what they will be measured against can be reached by the levers within their control. We would never evaluate a bank teller by the number of light bulbs that need to be changed monthly, so test your goals to ensure a direct line back to employee actions and responsibilities.

- Know what people want. A huge problem is that organizations generally don’t know what their people want. For example, leaders may assume everyone is motivated by the same things or rely too heavily on what has historically been motivating. Particularly in large or longstanding organizations, there is too much application of the golden rule (treat others as you want to be treated) by decision-makers and not enough of the platinum rule (treat others as they want to be treated). There’s no secret to fixing this problem; you need to do your research (e.g., ask employees, read research on generational shifts, talk to industry leaders) and pilot before full-scale launch. The best approaches customize incentives for specific groups or individuals.

- Keep support and growth at the center. Earning an incentive should not be the end of the journey for your employees. Milestones are important, but should always be coupled with a “what’s next?” conversation so that people feel you are genuinely invested in their growth and development (which we hope you are!) and can tangibly see the road ahead. If one does not yet exist, take the opportunity to co-create. A common pitfall is focusing too much on monetary or extrinsic rewards, sometimes to the detriment of strong intrinsic motivators. Focusing on continual improvement and long-term development will help mitigate this risk.

How have you effectively implemented incentives? What’s been the most interesting outcome? Sound off in the comments below!

Making Teacher Leadership a Success

In our first post on teacher leadership, we noted a few key ideas and benefits of extending the impact of teachers. Here, we break down three suggestions for launching a new teacher leadership initiative as well as criteria to measure success and common pitfalls to avoid.

How do you launch a successful teacher leadership program?

Our research and experience suggest three critical steps to starting a new approach to teacher leadership:

- Start with a goal in mind: Avoid launching a new program without a clearly defined, and important problem to solve. For example, if your district finds that teachers are not feeling valued in decision making, a teacher leadership program aimed at increasing teacher voice would be more appropriate than a peer coaching initiative.

- Identify the right “strand” of teacher leadership: Teacher leadership can be instructional (coaching, learning communities, etc.), associative (organizing, community building, etc.) or policy focused (advocacy, implementation feedback, etc.).

- Build a leader profile and plan for their development: Identify the specific knowledge, skills, and mindsets teacher leaders will need to be successful. Consider the personal or professional goals teacher leaders could be working towards and how they’ll be held accountable to meeting the expectations for their role.

Criteria for Success

Successful implementation of any initiative requires specific benchmarks in order to direct action, mobilize energy and inspire persistence. At the same time, setting goals is not enough. In addition to guidance, training and coaching, people need the capacity to act.

Here are four criteria that leaders can use to achieve success:

- Alignment: Ensure teacher leadership priorities are aligned with overall school priorities.

- Goals: Collaboratively set and track progress against clear, measurable goals for teacher leadership.

- Systems of Support: Identify a clear, cohesive system of support for teacher leaders to drive their professional growth and success.

- Schedules: Carefully plan and agree upon scheduling to guarantee teacher leaders have the time to succeed.

Common Pitfalls

The work we do as educators is difficult. Leaders often find themselves constrained with limited budgets and capacity to drive change; while teachers often wish for another hour in the day to make that additional phone call home or photocopy for the next day.

In launching a teacher leadership program or opportunity, look for, and avoid the following common pitfalls:

- Temporary: Teachers notice when positions are tenuous. Avoid funding sources that may not persist long enough to influence recruitment and retention.

- Detached: Roles that prevent teacher-leaders from spending a portion of their time teaching students make it much harder for them to keep teaching skills fresh and stay connected to student needs.

- Low reach: Many teacher-leadership roles actually reduce the number of students for whom the best teachers are responsible. If fewer students benefit from the best teachers, fewer will make the learning gains these teachers induce.

- Short on time: Too many teacher-leader roles are heaped on top of teachers’ other responsibilities. Co-planning, modeling, co-teaching, coaching, and collaboratively adjusting instruction based on student data require more planning time.

- Low or no pay: Most teacher-leader roles are low- or no-pay roles; this sends the message that teacher leadership is expendable, rather than essential to schoolwide success.

- Low authority, low accountability: Teacher-leaders’ formal authority and evaluations rarely align with responsibility for wider student spans and a positive impact on peer and students success.

How has has teacher leadership made in impact in your school or career? What led to success? What should be avoided? Sound off in the comments!

Sources:

- York-Barr, J. and Duke, K. “What do we know about teacher leadership”. Review of Educational Research. (2004)

- Karen Seashore Louis, Kenneth Leithwood, Kyla L. Wahlstrom, and Stephen E. Anderson, “Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning,” University of Minnesota (2010).

- Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, and Anderson, “Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning”

- Leading Educators and the Aspen Institute, “Teacher Leadership that Works,” Aspen Institute (2014).

- C. Kirabo Jackson and Elias Bruegmann, “Teaching students and teaching each other: The importance of peer learning for teachers,” National Bureau of Economic Research No. 15202 (2009);

- Cory Koedel, “An empirical analysis of teacher spillover effects in secondary school,” Economics of Education Review, Vol. 28, 682–692 (2009);

- Kun Yuan, “A value-added study of teacher spillover effects across four core subjects in middle schools,” Education Policy Analysis Archives, Vol. 23, no 7 (2015).

Five Lessons for Decision-Making

Making decisions is hard (just ask my husband how many rugs I’ve looked at for our living room). It’s even harder when those decisions will have a real impact on students, teachers and school leaders. Yet working with school system leaders across the country, it’s become very clear to us that how organizations make decisions has a huge impact on the success of their initiatives and of their organization overall. A few things we’ve learned:

1. Choose one final decision-maker. We all like the idea of consensus. We want to believe if we discuss ideas thoroughly, eventually we will come to a clear answer everyone believes in. Unfortunately, that lofty goal can instead lead to delays, frustration and in the end, no clear decision. Before diving into a project, leaders need to very clearly identify who is the final decision-maker for each key decision. The decision-maker should have input from as many stakeholders as possible in order to make the best possible decision, but at the end of the day, he or she has to make a final call.

2. It doesn’t have to be the head honcho. The most effective organizations we’ve seen delegate not only work, but also decision-making. For example, we work with a great organization where the CEO trusts the Chief Talent Officer to make smart decisions. He also trusts her judgment to bring particularly difficult decisions to him to discuss and decide together. As a result, the Chief Talent Officer is invested, feels ownership over her work, and makes things happen quickly. She’s not bottlenecked by a lengthy decision-making process when it isn’t necessary and because she’s closer to the work, is able to make great decisions. As leaders, consider who is best positioned to make the right call and institute a path for escalation when necessary.

3. There isn’t a right answer. Sorry to break it to you, but unfortunately there is not always a right answer. There is only the best possible decision given the available information. We’ve seen leaders in decision paralysis because they are afraid to make the wrong decision; instead, they repeatedly to ask for more and more information to delay their decision. As a result, there is less time for planning, communications, change management and implementation (all of which are often equally if not more important than the decision being made). The overall success of the work is damaged when decisions are delayed unnecessarily.

4. Once a decision is made, all leaders must rally behind it. Behind closed doors, share concerns candidly and fight it out. But once a decision is made, all leaders must present a united front to support the decision. Nothing hurts credibility of a decision more than a leader questioning a decision publicly.

5. Decisions must be tested and can be changed. The good news is that most decisions are not forever. With changing environments, new information or different players, things will always need to evolve. We encourage our partners to thoroughly pilot their initiatives and to use that new information to improve their decisions in the best interest of teachers, leaders and students.

Making decisions is hard, but there are ways to make smarter, better decisions. What lessons have you learned about making decisions? Sound off in the comments.

-Sarah

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part III: Amplifying Stakeholder Voice with Surveys

This post is the third in a series on how innovators are reimagining the design and implementation of evaluation and development frameworks. Read our earlier posts on observation frequency and raising rubric rigor.

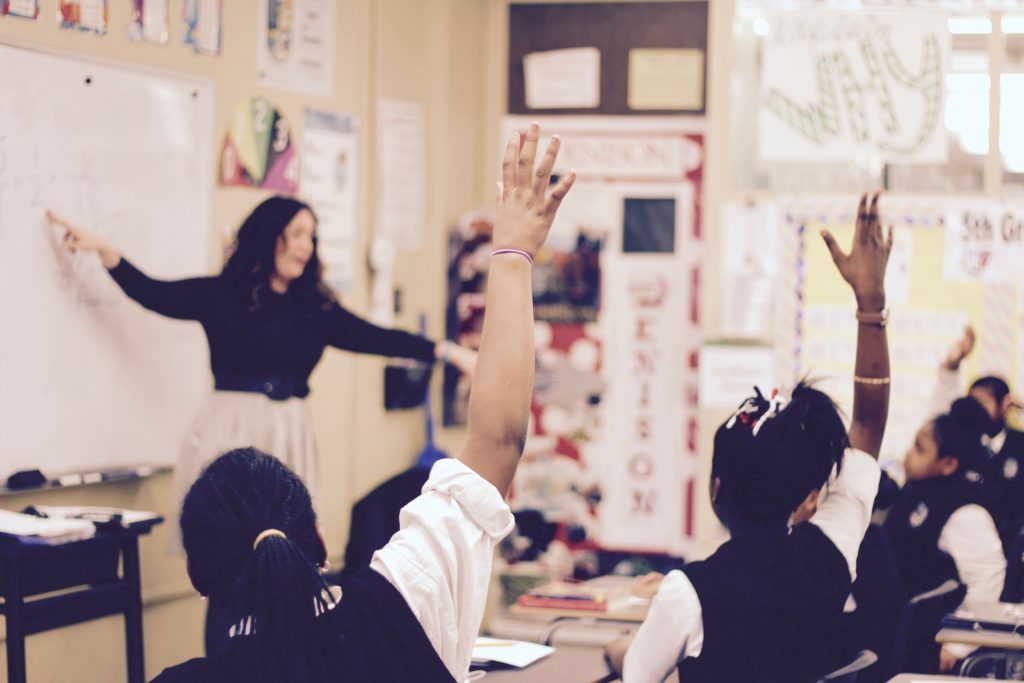

When you think of a teacher, where are they? What are they doing? If you envisioned someone standing in front of a blackboard, lecturing a group of students, you’re likely not alone. In reality however, teachers spend their days in a multitude of ways: working individually with students, collaborating with peers, planning independently, connecting with parents and family members.

Definitions of excellent teaching therefore must go beyond classroom observations and measures of student outcomes (both of which are important!), to gather a broader view of a teacher’s impact.

Surveys are a simple, yet powerful tool that can amplify the voices of stakeholders from across a school community to help educators develop a comprehensive view of excellence.

The Benefits of Administering Surveys

- Surveys, coupled with other measures like classroom observations, provide rich information to help teachers improve their practice. Teaching is a complex job that depends on strong relationships. While districts and schools have made progress in collecting data and providing feedback on certain aspects of the profession (e.g., content knowledge, teaching strategies, assessment data), our field often misses the opportunity to coach teachers on their relationship building with students, families and peers.

- Research says that students are reliable evaluators of a teacher’s impact. Analysis by the Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project finds that teachers’ student survey results are predictive of student achievement gains. In other words, students know an effective classroom when they experience one.

- Surveys provide the opportunity to put values into practice. Value statements like “we are a team and family” or “parents are partners” are powerful; however, these beliefs are only as true as the actions taken to build an authentic community. Administering surveys of key stakeholders sends a strong message that the voices of community members are valued, respected and heard.

- Surveys provide clear and transparent expectations to teachers. When questions are shared with teachers in advance, the survey content provides clear definitions for expected behaviors in teacher-to-teacher, teacher-to-student, and teacher-to-family relationships. For example, if a survey asks families if they receive one or more positive phone calls a month from their child’s teacher, that sets a very clear expectations for the teacher-family relationship.

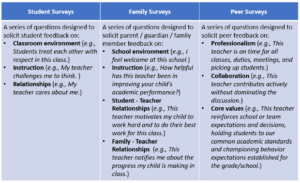

Survey Types

Educators have available a number of survey types, structures, question formats and administration platforms.The table below highlights three common survey types.

Surveys should be designed thoughtfully, taking into consideration the purpose, audience, and respondents.

- Purpose – Why are you administering the survey? What do you hope to learn? How will results be utilized?

- Audience – Who will analyze and interpret the survey results? When and how will they reflect on and plan from the results? How will the results be debriefed with teachers to improve practice?

- Respondents – Who will complete the survey? When and how will they complete the survey? What directions, supports and technology will be necessary for administration?

To learn more, including a list of sample survey questions, visit the resources page of our website.

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part II: Raising Rubric Rigor

This post is the second in a series on how innovators are reimagining the design and implementation of evaluation and development frameworks. To read our first post in the series, on the impact of frequent observations, click here.

Most teacher evaluation systems today include direct observations of teacher practice by an administrator, in which the administrator determines ratings by assessing what they observed against a common performance rubric. It is challenging to capture the complexity of teaching in a single document, however strong rubrics have the capacity to set clear expectations, establish a common language, and chart a course for development over time.

During our work with school systems across the country, we have seen a few common challenges with widely-used rubrics:

1. Structure: Rubrics can be too long, wordy, and easy to master.

When rubrics are too lengthy, they can be overwhelming or intimidating to educators, fail to prioritize high-leverage teacher actions over lower-impact strategies, take too long for observers to complete and are challenging to norm across multiple raters. Additionally, when rubrics are too “easy”–that is when basic instruction with minimal impact on student learning aligns to language at the highest levels–we rob educators of a true pathway for growth in their careers and limit their potential for excellence.

2. Framing: Rubrics generally focus only on teachers.

When rubrics describe only what teachers are doing and saying they fail to take into account what matters most: the impact of instruction on students. This can limit the value of observation feedback and lead to misalignment between observation ratings and other components of an evaluation framework.

3. Content: Rubrics are often not aligned to today’s raised academic expectations.

When rubrics do not call for rigorous instruction aligned to core content standards (Common Core, Next Generation Science, etc.) they miss the opportunity to set expectations for learning at the appropriate bar. Similarly, as our knowledge of social-emotional learning, cultural competency, and technology expand, many rubrics have yet to adapt and account for new knowledge and skills.

In the face of these challenges, innovators are creating a new normal for observation rubrics. Through our partnership with school systems across the country, we have seen that there is no one right way or perfect rubric. Rather, systems need to consider their unique culture, expectations, observer skill level and existing structures to find or develop a rubric that will work best for them.

DREAM Charter School: DREAM prioritized finding a streamlined observation rubric that would be appropriately rigorous as teacher advances along their career while less cumbersome than the tool they had previously been using. Following research into available tools and piloting of a select few, DREAM identified the TNTP Core Teaching Rubric as the right resource: it was aligned to academic content standards, written in the form of student outcomes, and best of all, was only four pages long! DREAM revised some language to incorporate school-specific competencies that drive their unique student and adult culture. Following the first year of implementation, nearly 80% of teachers said the rubric defines excellent instruction well.

KIPP Houston Public Schools: The original and largest KIPP region is currently piloting the Reach to Rigor rubric, a new tool created in-house that defines academic and cultural expectations for teachers and students. The rubric is broken down into four parts with only the most critical components of great instruction included. The rubric language also includes both teacher and student actions, to ensure that instructional moves by the teacher are only deemed high-quality if they have the desired effect on student thinking and behavior.

Achievement First: One of the first movers in formalizing a career pathway for teachers, Achievement First has refined their approach to observation and feedback over time. The network developed and launched an updated AF Essentials Rubric that was intentionally designed to be concise, clear, focused on student actions. The rubric is aligned to the Common Core and expectations of Advanced Placement courses, shifting more emphasis to intellectual rigor and deep student thinking. The rubric includes both “foundational” (e.g., tight classroom or kids on task) and excellence (e.g., investment and deep student thinking) criteria.

What are other innovations in observation rubrics? Add your ideas and/or experiences in the comments section below.

Welcome to the Hendy Avenue Blog

Welcome to Hendy Avenue Consulting’s new blog!

Over the past four years, we have have been fortunate to partner with wonderful school systems across the country to help them grow and retain talent. And we’ve learned a lot! We are excited to launch this site as an opportunity to share what we’re learning, disseminate research, highlight best practices, present case studies of promising practices and post interviews with leaders in the field.

In the coming weeks, we will publish posts on how school systems can put teacher development at the core of evaluations, a case study of how KIPP Austin is investing in teachers, and a run-down of some of the recent research we have been reading.

We hope you enjoy each post, leave comments, and share with those in your network.

At Hendy Avenue Consulting, we believe that investing in talent has the potential to dramatically change the landscape of education in our country and the lives of millions of children. You can learn more about us and our work here.