Posts Tagged ‘rubrics’

Collaborating to Examine Teacher Observation Rubrics for Equity

As an organization that strives to be anti-racist and to advance diversity, equity, inclusion and justice in our work, our Hendy team has taken a close look at our priorities and projects to determine how we can take steps to actively help create anti-racist schools. We believe that every organization should consider where they have influence and take strides to use their influence to proactively address racism, and teacher evaluation rubrics is ours.

As experts in teacher evaluation, and as an organization that frequently supports networks, districts and states to design and implement teacher evaluation rubrics, we identified rubrics as a place that we can advance equity with our clients. We know a lot about rubrics, both about how to write good rubrics, and how to implement rubrics to support teacher development and growth. And, we’ve been intentional about including language about inclusion and diversity in rubrics that we’ve helped to draft and implement. But we hadn’t yet taken an intentional look at rubrics to identify what in the language may be truly advancing equity in teaching and learning, and what might be hindering equity. We also knew that, as a team of four people who all identify as white, we have some critical blindspots in the work of examining tools with an anti-racist lens.

So, before we set out to create a tool, host a workshop, or even publish this blog post, we decided to do the work of examining rubrics ourselves. We contracted with two trusted leaders in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in education, Carrie Ellis from Celestial Consulting and Ashley Griffin from Bowie State University and BEE Consulting, who themselves are women of color, and asked them to engage in this work with us. We also engaged Talia Shaull from Achievement First and Lisa Friscia from Democracy Prep, both members of Hendy’s Chief Talent Officer cohort, so we could have the perspective of practitioners in the field leading this work in their organizations. As a team we set out to examine the language of four teacher observation rubrics, two that are commonly used in districts and networks across the country, and two that are specific to networks we work closely with. Our intent was to identify specific examples of language, and overall trends in rubrics, that either supported or hindered efforts to advance equity and anti-racism. We also wanted to test a potentially transferable process for examining rubrics with an anti-racism lens.

We started the work by first affirming the role of rubrics in advancing equity and anti-racism in schools, and were honest about what rubrics can and can’t do. Then we examined the content of four rubrics to identify:

- Language or expectations in the rubric that values white dominant norms, values, and culture over those of other racial groups;

- Language in the rubric that is supportive of equity (specific practices, mindset cues for teachers, etc.); and

- Missed opportunities in the rubric to advance equity of instruction for students.

We organized and summarized the themes we saw in each rubric, and discussed those themes together to both align and clarify. In our discussion we surfaced several categories of content that might drive examination of other rubrics for bias and equity.

In addition to categories of content, we also discussed structural features of rubrics, and how those features may or may not advance equity. Specifically, we discussed student-focused vs. teacher-focused rubrics, and the inclusion of DEI as a separate indicator vs. baked in throughout all indicators.

Bringing together experts in different content areas to wrestle with a challenging question was engaging and frankly a lot of fun. We were able to push each other’s ideas, discuss what really matters, debate language and its impact, and learn and grow in the process. At the end of the day, our brains were tired, but we were energized by the ideas we created together and the possibility of sharing with others. We see a significant opportunity to improve rubrics and recognize that while doing so is insufficient for creating anti-racist schools, they do play a critical role in driving teacher practice and leaders’ coaching, and therefore must be improved.

Our work helped us to develop guidance that might support others who wish to examine their own teacher observation rubric, and inspired us to engage others in this work. We look forward to sharing that guidance in a webinar later this spring. If you or your team would like to engage in this work, please reach out. We all have a role to play in advancing anti-racism in our schools, and teacher evaluation rubrics can be a great place to start or continue efforts to ensure equity for all students.

Huge THANK YOU to Carrie, Ashley, Talia, and Lisa from all of the Hendy team!

Three Steps to Avoid Common Observation Biases

We all have biases. Whether picking an ice cream flavor or choosing to take the scenic route rather than the highway, we all operate with mental models that place disproportionate weight on certain factors that move our judgment in favor of one option when compared to another.

When observing and evaluating teacher practice, there are numerous opportunities for biases to creep in. Just think of all the factors that go into a lesson: the subject, grade, school, teacher, time of day, lesson structure, materials used and more. An observer may think to themselves, “the students were well-behaved for the first class right after lunch”. A different person observing that same lesson may think, “if I was teaching this class, I would have used a different text.” Both of these sentiments may be true, but they have to be placed aside before conducting a visit so that observers can focus on objective teacher and student actions.

In short, great observers, coaches, and evaluators must identify, then set aside, biases in order to fairly and accurately evaluate and develop teacher practice.

Common biases include:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions,

- Halo effect: the tendency for a person’s positive or negative traits to “spill over” from one area of their personality to another in others’ perceptions of them, and

- Mirror bias: the tendency to judge performance as “good” if it is “like I would have done it.

A full table of common observer biases with examples can be found here: Observer Bias Examples

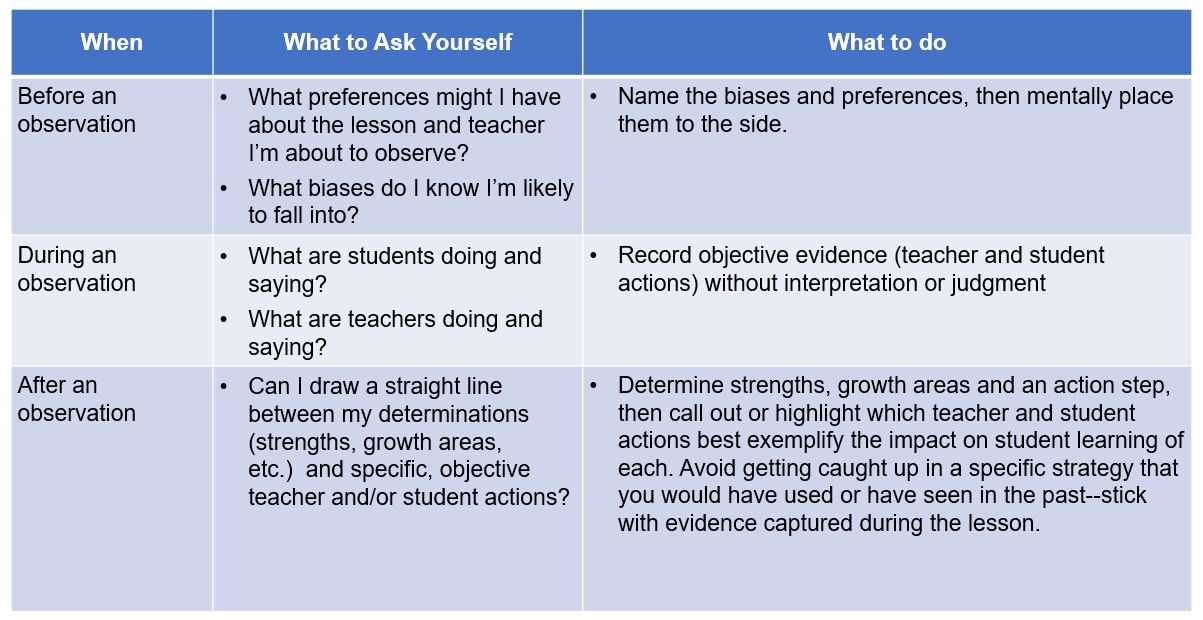

In order to mitigate the impact of these biases, great observers should ask themselves three questions:

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part II: Raising Rubric Rigor

This post is the second in a series on how innovators are reimagining the design and implementation of evaluation and development frameworks. To read our first post in the series, on the impact of frequent observations, click here.

Most teacher evaluation systems today include direct observations of teacher practice by an administrator, in which the administrator determines ratings by assessing what they observed against a common performance rubric. It is challenging to capture the complexity of teaching in a single document, however strong rubrics have the capacity to set clear expectations, establish a common language, and chart a course for development over time.

During our work with school systems across the country, we have seen a few common challenges with widely-used rubrics:

1. Structure: Rubrics can be too long, wordy, and easy to master.

When rubrics are too lengthy, they can be overwhelming or intimidating to educators, fail to prioritize high-leverage teacher actions over lower-impact strategies, take too long for observers to complete and are challenging to norm across multiple raters. Additionally, when rubrics are too “easy”–that is when basic instruction with minimal impact on student learning aligns to language at the highest levels–we rob educators of a true pathway for growth in their careers and limit their potential for excellence.

2. Framing: Rubrics generally focus only on teachers.

When rubrics describe only what teachers are doing and saying they fail to take into account what matters most: the impact of instruction on students. This can limit the value of observation feedback and lead to misalignment between observation ratings and other components of an evaluation framework.

3. Content: Rubrics are often not aligned to today’s raised academic expectations.

When rubrics do not call for rigorous instruction aligned to core content standards (Common Core, Next Generation Science, etc.) they miss the opportunity to set expectations for learning at the appropriate bar. Similarly, as our knowledge of social-emotional learning, cultural competency, and technology expand, many rubrics have yet to adapt and account for new knowledge and skills.

In the face of these challenges, innovators are creating a new normal for observation rubrics. Through our partnership with school systems across the country, we have seen that there is no one right way or perfect rubric. Rather, systems need to consider their unique culture, expectations, observer skill level and existing structures to find or develop a rubric that will work best for them.

DREAM Charter School: DREAM prioritized finding a streamlined observation rubric that would be appropriately rigorous as teacher advances along their career while less cumbersome than the tool they had previously been using. Following research into available tools and piloting of a select few, DREAM identified the TNTP Core Teaching Rubric as the right resource: it was aligned to academic content standards, written in the form of student outcomes, and best of all, was only four pages long! DREAM revised some language to incorporate school-specific competencies that drive their unique student and adult culture. Following the first year of implementation, nearly 80% of teachers said the rubric defines excellent instruction well.

KIPP Houston Public Schools: The original and largest KIPP region is currently piloting the Reach to Rigor rubric, a new tool created in-house that defines academic and cultural expectations for teachers and students. The rubric is broken down into four parts with only the most critical components of great instruction included. The rubric language also includes both teacher and student actions, to ensure that instructional moves by the teacher are only deemed high-quality if they have the desired effect on student thinking and behavior.

Achievement First: One of the first movers in formalizing a career pathway for teachers, Achievement First has refined their approach to observation and feedback over time. The network developed and launched an updated AF Essentials Rubric that was intentionally designed to be concise, clear, focused on student actions. The rubric is aligned to the Common Core and expectations of Advanced Placement courses, shifting more emphasis to intellectual rigor and deep student thinking. The rubric includes both “foundational” (e.g., tight classroom or kids on task) and excellence (e.g., investment and deep student thinking) criteria.

What are other innovations in observation rubrics? Add your ideas and/or experiences in the comments section below.

Designing Evaluation Frameworks with Development at the Core – Part I

Encouraged by Race to the Top and the Department of Education’s ESEA waivers, teacher evaluations moved into the education policy limelight during the last decade. Dozens of states updated antiquated systems–usually nothing more than a checklist of low-impact items–into multiple measure approaches with student achievement a preponderant component.

While this was a critical first step, too many frameworks failed to prioritize teacher development, becoming compliance exercises for school leaders. Fortunately, innovators across the country are re-imagining the design and implementation of evaluation frameworks into evaluation and development frameworks.

Over the next few months, we will share examples of these innovations from various partners and leaders in the field. In our first post on the topic, we share how two school systems are using frequent, unannounced observations to drive teacher development.

The Power of Frequent Observations

Observations have historically been rather formal exercises, often with scheduled pre- and post-conferences designed to provide teachers and administrators with dedicated time to plan for and then reflect upon a lesson. While there is immense value in these face-to-face interactions, they come with limitations. The heavy time burden for scheduling and completing these meetings limits the frequency in which they can occur. Often, administrators will only be able to visit one to three times in year, reducing the impact of their feedback and diminishing their ability to provide meaningful follow-up support. Announced observations also increase the opportunity for a lesson to be less reflective of a teacher’s true daily practice.

Many school systems across the country are taking a different approach to observations:

The Teaching Excellence Framework is used by more than a half-dozen independent charter schools in Delaware as part of the state’s educator evaluation regulation (Chapter 12, subchapter VII, Section 1270(f)) that allows LEAs to apply to implement an alternative teacher evaluation system. The framework was designed with frequent lesson observations at the heart of the overall plan for teacher development. Observations are 15-20 minutes in length and occur at least 8 times throughout the year. Following each observation, the observer utilizes the Teaching Excellence Rubric to assess the evidence in the lesson. A face-to-face debrief conversation occurs within one week in which the teacher and school leader determine concrete, actionable next steps. As a result, 95% of teachers surveys reporting feeling ‘positive’ to ‘very positive’ about the shift to the Teaching Excellence Framework. You can learn more about the Teaching Excellence Framework here.

Understanding the importance of excellent teachers, in 2014 the DREAM Charter School in New York City set out to revamp their system for teacher evaluation and recognition. Recognizing their teachers wanted more frequent feedback, the design committee at DREAM developed a system that would include:

- Five unannounced observations throughout the year in which a teacher’s manager or a secondary observer determine ratings on the DREAM Observation Rubric

- Bi-weekly unannounced observations in which a teacher’s manager provides feedback and direct support, including real-time coaching (no ratings)

All observations are followed by coaching conversations focusing on strengths and growth areas of the teacher’s practice as well as instructional next steps. Following the first year of implementation, one teacher praised the approach noting “it gives teachers clear take aways and next steps” while another said “it is streamlined [and] it pushes for development.” To learn more about DREAM Charter School, you can visit their website here.

What are other innovations around observation frequency? Add your ideas and/or experiences in the comments section below.